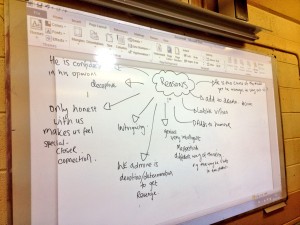

Recently, I decided there were 3 things I’d really like all of my students (not just those who always get A’s) to understand about essay writing. They were

STANCE – you have to take up a position, interpret events, offer an opinion. The same facts can lead to different conclusions for different people (mostly agree, balanced view, mostly disagree)

STRUCTURE – you must create tightly woven paragraphs, with depth, flow and sophistication. See the “perfect paragraph project” for a simplified version of this idea.

SEQUENCE – for character and theme essays you’ll probably follow the chronological order of the play. You don’t have to, but it probably helps to follow the order in which events unfold. Also, starting with the murder of Lady Macduff, then jumping back to Duncan’s murder, then hopping to the sleepwalking scene and then back to the Banquet scene wouldn’t make a whole lot of sense, now would it? The danger here is that you need to avoid telling the story. ONLY include details relevant to answering the question.

(WARNING: certain questions require a non-chronological response, for example “Relevance to a Modern Audience” or “Shakespeare’s play offers a dark and pessimistic view of human nature” because each paragraph will most likely focus on a different character or theme or scene).

To teach these concepts, I came up with the following lesson, designed for a double class period:

Below you’ll find 15 paragraphs on Lady Macbeth all mixed up in no particular order.

5 of them, arranged in the correct sequence, create an essay which takes a very positive interpretation of her motivations and behaviour.

5 of them, arranged in the correct sequence, create an essay which takes a balanced view of her motivations and behaviour.

5 of them, arranged in the correct sequence, create an essay which basically slates her!

I didn’t include introductions or conclusions – I felt that would makes the ‘jigsaw‘ too easy.

I gave the fifteen paragraphs, out of sequence, to my Leaving Certs. I asked them to decide which 5 paragraphs belonged in the positive essay; the balanced essay; and the negative essay. (Thus they were reading for a specific purpose)

Then they had to arrange them in the correct order. As they completed the exercise, I gave them a photocopy of each essay in the correct sequence so they could check the correct order and see how they’d done.

Next I asked them to highlight any words/phrases or ideas they didn’t understand and I explained what they meant. (Again, reading for a specific purpose)

Their next challenge was to figure out what the essay title was!

Finally, I gave them 3 essay titles. For homework they had to select one and write an essay as a response.

Here are the essay titles I gave them:

“Lady Macbeth is the architect of her own downfall” – Discuss

“We feel little pity for Lady Macbeth in the early stages of the play, but as her remorse grows, so does our sympathy for her” – Discuss

“Lady Macbeth is motivated by selfish ambition and lacks a moral conscience” – To what extent do you agree with this assessment of her character?

Below you’ll find the paragraphs in mixed up sequence:

Lady Macbeth did not make a positive first impression on me. She sees nagging as a form of bravery, vowing to “chastise [Macbeth] with the valour of [her] tongue” and views kindness as a weakness, criticising her husband for being “too full of the milk of human kindness to catch the nearest way”. This moral confusion and inability to distinguish between right and wrong makes her in some ways similar to the witches who claim that “fair is foul and foul is fair”. However, unlike them, evil does not come easily to her – she knows she will need help to behave in an immoral way, hence her demand “come you spirits that tend on mortal thoughts…. fill me from the crown to the toe top full of direst cruelty”. Furthermore, she may be doing the wrong thing but she’s doing it for the right reasons: she is utterly devoted to her husband. She knows he wants to be King but may not be willing to do what she feels is necessary to realise this goal (“thou wouldst be great, art not without ambition but without the illness should attend it”) and hates the thought that he might live to regret his inaction in the face of the prophecy. Thus, although I don’t approve morally of Lady Macbeth’s behaviour I found it easy to understand her, to empathise with her motivation and thus to like her somewhat despite her flaws.

From the very first moment she appeared on stage, Lady Macbeth struck me as a manipulative, domineering wife with zero moral conscience. She immediately jumps to the conclusion that they will have to engage in acts of “direst cruelty” in order for Macbeth to become King, despite the fact that her husband never suggests that they use violence to achieve “what greatness is promised”. This evil streak is further evident in her commentary on her husbands’ personality: she views his humanity and empathy as negative traits, describing that fact that he is “too full of the milk of human kindness to catch the nearest way” as a weakness. Her eagerness to “pour my spirits in [Macbeth’s] ear”, her willingness to be possessed by evil spirits (“come you spirits that tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here…”) and her delight in embracing the darkness (“come thick night and pall thee in the funnest smoke of hell”) are all to me strong evidence of her fundamentally immoral outlook and domineering personality. I certainly would not like to be married to her.

Lady Macbeth’s reaction to Macbeth’s letter about the witches prophesy introduced me to a devoted wife who will go to any lengths to help her husband achieve his potential. Her belief that her husband is “too full of the milk of human kindness to catch the nearest way” and lacks the ruthlessness necessary to fulfil his ambitions is what drives her on. She is determined to “chastise [him] with the valour of [her] tongue” because she hates the idea that her husband will one day look back on his life and feel as if he let opportunities for greatness pass him by. It’s also clear that Lady Macbeth in not inherently evil – she in no ways relishes the idea of committing the sin of regicide. In fact, she knows she will need to be possessed in order to see it through, hence she proclaims “come you spirits that tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here and fill me from the crown to the toe top full of direst cruelty”. Thus, my initial reaction to Lady Macbeth was quite positive: here was a woman willing to do whatever it took to support her husband in achieving his dream of one day becoming King.

Whilst some critics point to Lady Macbeth’s failure to carry out the actual murder, this does not endear her to me. Duncan’s coincidental similarity to her father (“Hath he not resembled my father as he slept, I had done’t”) is not enough to make her re-consider their plan. She fakes comforting words (“these deeds must not be thought of after these ways; so, it will make us mad”) to try and snap Macbeth out of his reverie but in my opinion she is motivated entirely by self-interest here – she doesn’t want them to get caught. Her lack of compassion reappears as she lambasts her husband for bringing the murder weapon from the crime scene (”infirm of purpose! Give me the daggers”) and without hesitation, she returns to Duncan’s chamber to “gild the faces of the grooms” with blood, thus framing them for the murder. She will do whatever it takes to get away with murder, including her false fainting spell, designed to draw attention away from Macbeth. She is a selfish, ruthless, immoral individual whose lack of empathy or remorse is best summed up in her flippant remark “a little water clears us of this deed”. As you can see, I do not like this woman, nor do I buy into the notion that she is guiltless simply because she did not “bear the knife [herself]”.

However, ultimately I found myself devastated to witness her intense suffering during the sleepwalking scene, and this I took as proof that despite her significant flaws, I had grown fond of her. I found her horror as she relived their crimes (“the Thane of Fife had a wife, where is she now?”) and her devastating realisation she would never again be free of this guilt (“All the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand”) truly heartbreaking. She made a mistake and this mistake destroyed her, her marriage, her happiness and her future. Thus I liked her despite her flaws, yet I could nonetheless understand why Malcolm described her as a “fiend-like queen” given the havoc and destruction wrought upon Scotland by her and Macbeth’s crimes.

This devotion to her husband is again evident when she convinces him to murder Duncan. Although her tactics are quite manipulative (suggesting he doesn’t truly love her if he doesn’t keep his promise) Lady Macbeth is once again concerned only for the regret he will feel if he backs out now. She warns him that he will have to “live a coward in thine own esteem” forever and worries about the negative impact this would have on his self-esteem. Her obsession with Macbeth’s future happiness is actually quite easy to understand. Firstly, she loves her husband. Secondly, she knows that he is deeply ambitious. Thirdly, it’s possible that she feels guilty that she has not provided him with a living heir; after all, a woman’s role in this era was primarily to get married and produce children. We know they have had at least one child (“I have given suck and know how tender tis to love the babe that milks me”) who, for reasons unknown, has died. It is possible that she feels guilty that she has failed to fulfil his dream to be a father and this in turn has made her doubly determined to see him achieve his other life’s goal, which is to be King. She may be convincing him to do the wrong thing, but she is doing it for good reasons and as a result I could not help but like her.

The sleepwalking scene is generally highlighted as the moment of greatest empathy and connection between the audience and Lady Macbeth but I personally found myself unmoved by her suffering. Yes, she is reliving their crimes, which is no doubt unpleasant, but she also reminds us here of her part in convincing Macbeth to kill Duncan (“Fie, my lord, fie! A soldier and afeard?”) and of her filthy smearing of his royal blood on the chamberlains (“Yet who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?”). In this context, is it any surprise that she asks the question “what will these hands ne’er be clean?” In my opinion, it is about time that the horror of her crimes registered with her properly, but it stretches the bounds of human empathy too far to expect me to feel pity for this “fiend-like queen”.

My fondness for Lady Macbeth increased tenfold when her intense remorse finally surfaced. She learns too late that “a little water” will be wholly inadequate to clear them of this deed as she realises that “noughts had, all’s spent, where our desire is got without content”. I empathised with her deep suffering as she began to envy Duncan’s peaceful sleep of death, observing sadly “tis safer to be that which we destroy than by destruction dwell in doubtful joy”. Yet she conceals her inner turmoil from her husband, pretending that everything’s fine so that he won’t worry about her. Her desire to comfort and protect him never wanes as she advises him that “things without all remedy should be without regard”. Even as he pushes her away (“Be innocent of the knowledge dearest chuck”) she continues to protect him, both during the banquet (“Sit worthy friends, my lord is often thus and hath been since his youth”) and afterwards (“You lack the season of all natures, sleep”). Her humanity has never been more evident and my sense of her as an essentially good, if misguided woman, was strengthened even further here.

Lady Macbeth’s humanity is briefly evident when she finds herself unable to murder Duncan and this glimpse of a conscience (“Hath he not resembled my father as he slept I had done’t”) made me like her a lot more. Her desire to help her husband (“these deeds must not be thought of after these ways; so, it will make us mad”) and save him from insanity is touching, as is her naive belief that they will be able to simply forget their crime (“a little water clears us of this deed”) and move on with their new life as King and Queen. However, just as I was starting to like her, she lambasted her husband for bringing the murder weapon from the scene of the crime (”infirm of purpose! Give me the daggers”) and without hesitation, she returned to Duncan’s chamber to “gild the faces of the grooms” with blood, thus framing them for the murder. Once again I found myself on a roller-coaster, unsure how to feel about the Machiavellian yet vulnerable Lady Macbeth.

Immediately prior to Duncan’s murder, Lady Macbeth’s behaviour is bullying, manipulative and quite shocking, making it difficult for us to like her. She mocks her husband, demanding dismissively “Was the hope drunk wherein you dressed yourself?”; emotionally blackmailing him by suggesting that he doesn’t really love her if he backs out; painting a horrific picture of a future filled with self-loathing (“and live a coward in thine one esteem”) if he passes up this opportunity; calling his manliness into question (“when you durst do it, then you were a man”) and most disturbingly of all, describing in vivid detail how she would commit infanticide – would pluck her nipple from her beloved child’s suckling mouth and dash his brains out on the floor – rather than break a promise to her husband. However, all of this is motivated by her love for her husband and her awareness of his ‘vaulting ambition’. I also found myself feeling very sorry for her when I discovered that she had given birth to and lost a child. Hence, almost despite myself, I found myself quite liking this determined forceful woman who would let nothing get in the way of her husband achieving his ambition.

Lady Macbeth finally begins to realise that evil actions have very real consequences (“nought’s had, all’s spent, where our desire is got without content”) but this was not sufficient to make me actually like her. Yet again her focus was entirely on her own happiness, and I found it particularly twisted that she would have the cheek to ‘envy’ Duncan (“tis safer to be that which we destroy than by destruction dwell in doubtful joy”) because he is ‘safe’ in death. I’m sure given the choice he would have swapped death for life in a heartbeat – but Lady Macbeth did not give him the option to live and now she has the gall to suggest that he’s better off dead! Her utterly selfish desire to protect her own power and position is again evident in the Banquet scene. She first blames Macbeth’s erratic behaviour on epilepsy and when it becomes clear that this is an inadequate explanation, she dismisses their guests unceremoniously “stand not upon the order of your going but go at once”. Combined with her sarcastic mockery of Macbeth (“Why do you make such faces? You look but on a chair”), I found Lady Macbeth an utterly contemptible character with few, if any, redeeming characteristics.

Even in the moment where Duncan is murdered, Lady Macbeth’s humanity is in evidence. She gets the chamberlains drunk, yet when it comes to committing a truly evil deed, she does not have what it takes to murder an old man in his bed, commenting sadly that Duncan “resembled [her] father as he slept”. Once there is no going back, yet again her wifely concern surfaces as she tries to shake Macbeth out of his trance insisting “these deeds must not be thought after these ways; so, it will make us mad”. She is naive in believing that “a little water clears us of this deed” but naivety is not a trait I normally associate with evil people and her fainting spell may well have been genuine shock when faced with the reality of their crime. Alternatively, even if her faint was fake, it was nonetheless inspired by a desire to protect her husband, lest anyone get suspicious following his admission that he killed the chamberlains. Thus, despite her immoral scheming, I continue to see her humanity and like her as a person.

The ultimate testament to Lady Macbeth’s character comes in the moments before her suicide. In the sleepwalking scene, I found her guilt as she relives their crimes (“The Thane of Fife had a wife, where is she now?”) and ultimately recognises that she will never again view herself as anything but a killer (“All the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand”) truly heartbreaking. She made a mistake and this mistake destroyed her, her marriage, her happiness and her future. I liked her despite her flaws, was devastated to hear that she “by self and violent hands took off her life” and could never see her as Malcolm did, as nothing more than a “fiend-like queen” .

My negative impression of her was further strengthened when she bullied Macbeth into agreeing to murder Duncan. She mocked her husband, demanding dismissively “Was the hope drunk wherein you dressed yourself?”; emotionally blackmailing him, suggesting that he doesn’t really love her if he backs out; painting a horrific picture of a future filled with self-loathing (“and live a coward in thine one esteem”) if he passes up this opportunity; calling his manliness into question (“when you durst do it, then you were a man”) and most disturbingly of all, describing in vivid detail how she would commit infanticide (would pluck her nipple from her beloved child’s suckling mouth and dash his brains out on the floor) rather than break a promise to her husband. Her manipulation of him was so profound, so morally bankrupt and so effective that within minutes she had transformed him saying “we shall proceed no further in this business” to moments later agreeing to kill Duncan “I am settled and bend up each corporal agent to this terrible feat”. How anyone could like this woman or defend her behaviour is absolutely baffling to me.

Lady Macbeth’s remorse, when it surfaces, does help us to like her, yet her failure to confide her doubts and fears in her husband is a frustrating aspect of her personality that lessens our fondness for her. She admits to us that “nought’s had, all’s spent where our desire is got without content” and that she would rather be dead like Duncan (“tis safer to be that which we destroy”) than living the hellish uncertainty she now inhabits (“than by destruction dwell in doubtful joy”), terrified at any moment that they will get caught. However, her pretence that everything is fine (“what’s done is done”) and later, during the banquet, her scorn for her husband’s suffering (“this is the very painting of your fear”…. “Shame itself! Why do you make such faces? You look but on a chair”) made me waver in my affection for her. Every time I find a reason to like her, she provides me with a very good reason not to.

PRINT THEM OFF – CUT THEM UP – SEE IF YOU CAN RE-ARRANGE THEM IN SEQUENCE!!!

Remember, there are no introductions or conclusions but you MUST include both.

Finally, the essay title was the very simple “Lady Macbeth is not a likeable character” – Discuss.