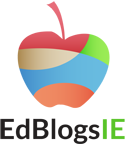

As an experiment with my brain, when I gave my leaving certs an unseen poem last Wednesday, I deliberately selected one I’d never seen before and wrote (well o.k. I typed, cause I don’t really hand-write at all anymore) my own personal response in 20 minutes.

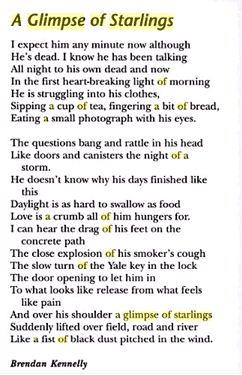

The poem was “A Glimpse of Starlings” by Brendan Kennelly which I have since discovered is on the ordinary level leaving cert course.

This little experiment proved to be way more fascinating than I originally anticipated. I thought I was just going to put myself in their shoes, and model some good practice. How wrong I was!

As I “corrected” their unseen poetry answers, I was astounded and impressed by the vast array of interpretations we came up with, several of which I’ve reproduced below, none of which we could verify were ‘correct’ as we were responding ‘blind’ to the poem, with no knowledge of the poet’s biography or access to interviews with him asking what the poem’s ‘really’ about!

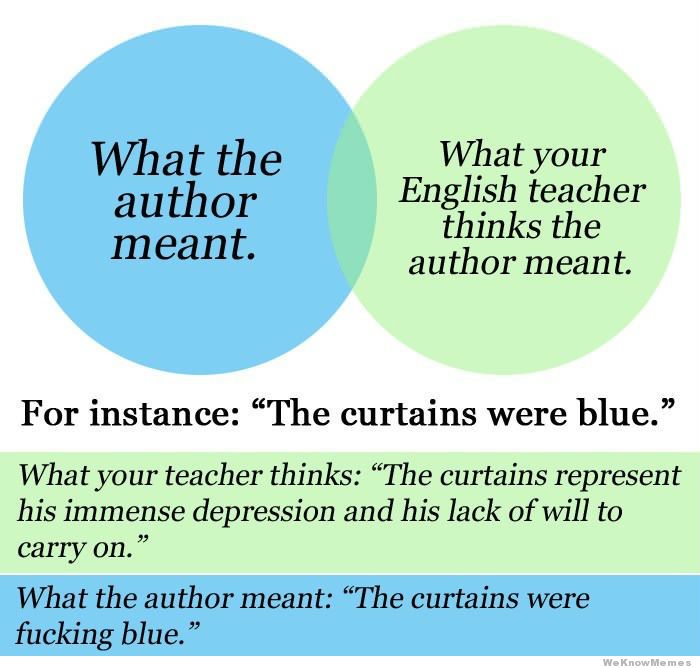

But this got me thinking about a truth we often whitewash, which is that there is no fixed, immutable meaning. I bring myself to every encounter with language and ascribe meaning to that encounter. It might mean something completely different to the other people in the exchange and I’ve got no control over how they respond to it! Every time I open my mouth, compose a text or a tweet, I know what I intend it to mean. And how often have I found myself saying, to quote TS Eliot “That is not what I meant at all; That is not it, at all“.

We do this don’t we? We get agitated when people take us up ‘wrong’. We re-phrase so they’ll see things the way we want them to. We try to bring them around to our way of thinking; try to control their interpretation of events.

How much distress has this caused the human race down through the centuries? How many mis-understandings and arguments has it engendered? Perhaps that’s why we obsess over achieving clarity in our communications, in our speaking and writing, because we want to minimise any potential gap between what we mean and what people think we mean.

But we need to face up to one crucial truth:

Meaning is not something that exists, it’s something that we create.

Then perhaps we can acknowledge that, for the most part, people are not deliberately ‘mis-interpreting’ us, they are simply bringing their own truth to the conversation. There will always be a gap between your intention and the meaning as it is received by the reader or listener. You cannot control this. The only thing you can do is try to make your intention as clear and unambiguous as possible.

Of course, poets are a different breed to the rest of us. They deliberately don’t do this. They wallow in the grey areas their art form creates. They LOVE ambiguity. They know that once you put something out into the world, you can’t control it anymore, or to paraphrase a well-worn trope they know that “language is in the ear of the beholder“.

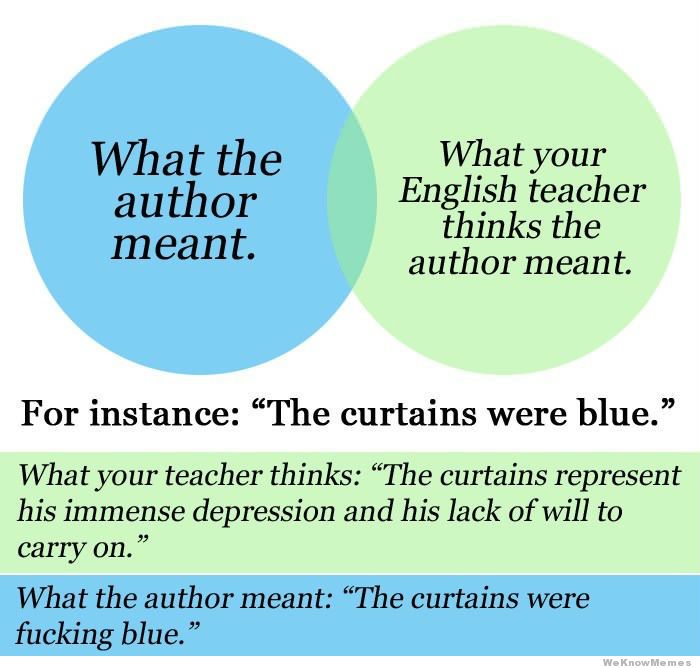

Reading poetry is a complex process; an interaction between the poet’s intentions and the readers’ struggle to impose meaning on what they’ve just read. The annihilation of poetry occurs when we ‘fix’ that meaning. And while we can mock this process …

… (yeah, the curtains were fucking blue!) we should also acknowledge that there might be something more going on here. Some dance of language between the speaker and the listener; some ever-changing, ever-moving complexity that is, in itself, a pleasurable tango that endlessly entertains even as it refuses to come to a standstill. Poetry makes multiple meanings, complex responses and a multiplicity of emotions possible.

And this is a GOOD THING if you ask me!

This experience also got me thinking about how the poetry textbooks we use, crammed with notes, shut down critical interpretations. They ‘fix’ the meanings of the poems. I’m guilty of this too with my poetry podcasts. In my eagerness to help students appreciate the prescribed poetry on a deeper level, I created mp3s of me discussing the poems, but there’s a danger that if students rely too heavily on listening to me, or any so-called ‘expert’, their own response, analysis and interpretation gets lost or demeaned.

This wasn’t my intention.

I created the podcasts to try and close the gap in time which opens up when you’re asked to revise a poet and write about them in an exam, sometimes a year, or even 18 months after you first study them. It was my intention that they would function almost as a kind of time portal so that the ideas we explored in class could be re-visited to refresh their memories.

But as the old cliché goes “the road to hell is paved with good intentions“.

Of course, this is why it’s important that students write at length and in depth about a poet immediately after they study his/her work. It’s so important their own unique response doesn’t get swallowed up, flattened out, diminished in a sea of notes (and podcasts!) so that it ends up conforming to the ‘norm’ rather than taking flight and becoming a truly original take on the poet in its own right.

So if you’d like to read some truly original takes on Brendan Kennelly’s poem “A Glimpse of Starlings“, have a look below.

Here’s what I typed in 20 minutes:

My personal response to this poem was one of confusion initially. The poet is remembering someone who has died, revealed in the first striking line as he admits “I expect him any minute now although / He’s dead”. There’s something shocking here, something heart breaking about the sad reality that we glimpse the dead continuously in our memories even though they’re not here anymore. I like how the poet made clever use of contrast (distinguishing between his expectation and the reality) to achieve this effect.

The poem does not settle into acceptance, however. Instead we get an atmosphere of gothic horror as we picture the dead man in some kind of afterlife “talking all night to his own dead” but the “first heart-breaking light” of morning brings no release or comfort. Personally I think he’s in some kind of limbo, although that may be me reading the poem too literally, because he’s desperate to know “why his days finished like this” but he gets no answer. As the contrast between what I expect for those who have died (either nothingness or heaven) and what this poem offers (“Daylight is as hard to swallow as food”) washes over me I am filled with despair. The simile of the “questions that bang and rattle in his head like doors and canisters the night of a storm” is so noisy, so ugly, so disturbing that I honestly didn’t want to read on anymore and the metaphor of starvation in the line “Love is a crumb all of him hungers for” is in my opinion the most haunting and heart breaking image in the entire poem, full of torment and longing.

The poet’s uncertainty about what lies beyond death is memorably captured in his allusion to the gates of heaven “The door opening to let him in” as simply being “what looks like release from what feels like pain” but the ambiguity captured in “looks like” and “feels like” leaves us with little comfort.

It is noteworthy, however, that the poem ends with “A glimpse of starlings” and that this is the title he chooses to give an otherwise bleak poem. It’s as if he’s looking for a sign in nature that all will be well, but I’m also reminded that this technique – pathetic fallacy – is called pathetic for a reason, because it is so foolish, illogical and ‘pathetic’ of us, as human beings, to think that our mood can in any way influence the weather or the seasons.

—

Sample answer 1 from one of my students

The poem’s opening line is in my mind extremely striking due to the poet blurring the lines between the possible and the impossible with the oxymoron “I expect him any minute now, although / He’s dead“. The line’s ambiguous nature draws me in and implores me to continue reading.

His unusual description of simple everyday actions such as viewing a picture, as “eating a small photograph with his eyes” lends the poem an originality which I find incredibly refreshing. From the poet’s detailed description of the man in the poem, I believe him to be an extremely complex and troubled man who longs for affection as “love is a crumb all of him hungers for”. Throughout the poem there is a tangible melancholic atmosphere which I feel emanates from the man’s evident misery.

However, the final image of the starlings rising into the sky “a glimpse of starlings suddenly lifted over field road and river” is to me a somewhat hopeful image that there may one day be happiness for this man. Nonetheless, the poet’s simile in the last line “like a fist of black dust pitched to the wind” gives me the impression that this man is lost without any direction in his life. which again gives this poem a mournful, bitter feeling at its conclusion.

—

I gave her 20/20 because she’s managed a perfect balance of the 3 Ts – Theme, Tone, Technique (also known as ideas, feelings and writing style) with a wonderful flow of language and concrete coherent yet complex vocabulary.

Sample answer 2:

I found this poem to be a very poignant one, whose message – that life is a continuous cycle – remained in my mind long after I had read it. The poet uses simple images of the everyday actions of this man who is now dead to depict the lonely gap that is left behind, as only memories of him remain.

He seems to have led an ordinary life, when alive. We are given a list of his daily actions “sipping a cup of tea, fingering a bit of bread, eating a small photograph with his eyes“. However, the depressing tone that seems to linger in these lines made me feel sympathy for this man. The questions that continuously “bang” and “rattle” in his mind are compared to “doors and canisters the night of a storm“. This image simile is an upsetting one. He seems to no longer have an aim in life and can barely manage to walk down the “concrete path” but awkwardly drags his feet. It is not a life that I would personally like to lead.

The final three lines had an emotional impact on me as I found them to be very sombre and hopeless. The man walks in the door and looks over his shoulder to see “a glimpse of starlings“, flying, carefree, in the air. A simile is used to compare them to a “fist of black dust pitched in the wind“. For me the black dust represents symbolises this man’s ashes as he is now dead. The memory of the man is slowly fading away and will soon have disappeared, just like these starlings in the air.

—

I gave this student 17/20. You’ll notice two occasions where I crossed out her word and put in a more precise one which would identify the poetic technique being used; so “image” became “simile” and “represents” became “symbolised”. My comment at the bottom of her answer was “use the language of poetry in your analysis. Otherwise excellent“

Sample answer 3:

The poem “A Glimpse of Starlings” by Brendan Kennelly is a poem which contrasts an alcoholic’s life with that of a bird (starlings) roaming free in the wind.

At first reading of the poem this theme suddenly became apparent to me. The alcoholic man is called “dead” indicating to me that he is simply wasting his life. He shares a relationship with “his own dead friends“. This line reminds me of the old men and women who sit all day in my local pub.

Together, drinking, they forget about the rest of the world and it isn’t until the “first heart-breaking light of morning” that the man realises what he has become. Unfortunately he cannot resist his addiction, instead he follows his routine and returns to the pub awaiting the “slow turn of the Yale key“. This man, however, longs to leave his ways behind as “Love is a crumb all of him hungers for“.

As he enters the pub, cinematically, over his shoulder we see birds taking off from a field afar. The comparison symbolism here is that the birds are free while the man feels trapped and locked in his alcoholism. Evaluating this poem, it brings evokes in me a feeling of sympathy and understanding towards those who suffer from addictions. They are trapped, imprisoned by their addictions. This poem allows us to gain respect and understanding for those who spend their lives suffering “like a fist of black dust pitched in the wind“. The starlings drift into the distance continuing with their business as the man begins to drink again.

—

I gave this answer 13/20. Her interpretation is really original and completely credible from the details included in the poem. However, the one solitary word which nods in the direction of commenting on the writer’s technique is “cinematic“. She didn’t use the word symbolism, that was me. So although she implicitly traces down through the poem as a metaphor, she never mentions that word, or uses any of the ‘lingo’ we associate with the act of interpreting poetry. Whether or not you think she should be penalised or not for an honest response which ignores ‘jargon’ is a discussion for another day. I’m torn on this one.

Sample answer 4:

The poem is an explosion of the senses for me, a contrast between silence and noise, life and death. The first paradox is presented in the first line of the poem: “I expect him any minute now although / He’s dead“. This thought is immediately conflicted in my mind by the verbs following, the onomatopoeia creating a tangibility that clashes with the idea of death (“struggling”, “sipping”, “bang”, “rattle“). I feel relief and a connection when I am told that “he” is as confused as I am: “He doesn’t know why his days finished like this“.

The allusion further down the poem strengthens the connection between me, the reader, and the elusive presence in the poem, with the reference to the “Yale key“, a brand name I am familiar with myself. Symbolism is hinted at in reference to the starlings, connecting him to the birds by referencing “over his shoulder” (meaning unclear…). The ambiguity of the “fist of black dust” gives another layer of confusion to the poem. Is it a fist of triumph thrown up into the air, finally getting in the house, or is it a threatening presence, a reminder of the perils that await him outside the house?

—

I found this one difficult to grade. There is a deep appreciation of the language of poetry, a bright mind asking as many questions as she answers. There’s an engagement with her feelings and with the feelings in the poem but zero attempt on any level to suggest what the poem might be about. So in terms of the 3T’s, she’s established tone and techniques on a deep level but has only briefly mentioned the theme of the poem (life and death) in her opening sentence. It’s a complete contrast to the answer above which focuses on meaning but ignores style almost completely. 16/20???

Sample answer 5:

Upon reading this poem for the first time, I believe that the speaker is the grim reaper who is patiently waiting for his next victim to drop: “I expect him any minute now“. As the victim struggles tries to perform simple tasks “he is struggling into his clothes” and nostalgically looks at his past “eating a small photograph with his eyes” I feel some deep empathy for him. It appears he is really struggling to go on for an unknown reason, perhaps heartbreak as “love is a crumb all of him hungers for“. It is clear this man is going through a tough time. It makes me think about the cruelty of this world, how death can happily wait for you to succumb as you can barely cope.

His use of the simile “daylight is as hard to swallow as food” really speaks to me. It paints an intense picture of how much pain he’s in, that swallowing a simple piece of bread is causing him great pain such distress, alongside his lack of willingness reluctance to go on as the brightness of day kills him inside. The writer’s use of vivid imagery is intense; “like a fist of black dust pitched in the world” really hits me on a personal note. I can almost feel the punch by the fist, like it is the last pang of agony he will ever experience, almost like a sense of relief.

—

Again, I found it hard to grade this one. On the one hand you have an original and intelligent interpretation, comparing the speaker to the grim reaper. She achieves a good balance of the 3Ts, although I would have liked to see a little more integration/analysis of techniques. The bits I’ve changed above have been altered for the most part because there’s a tendency here to get ‘stuck’ on particular words and to repeat them, instead of using synonyms. The last line takes a literal interpretation of the word ‘fist’ which doesn’t quite follow the logic of the simile it belongs to, but then the word is there for a reason, to make you picture a fist, so I don’t know…. 14/20 ???

—

A poem doesn’t have a FIXED meaning but it is possible to miss important distinctions if you’re not fully tuned in. A couple of students failed to distinguish between the “I” and the “He” in the poem. The speaker “I” is writing the poem about “Him”, the man he says is dead, the man he observes. They are not one and the same person and a careful reading of the poem reveals this but in the rush to respond, some students conflated the two.

Interestingly, if you google it, this is a poem about grief. So one student, although she did not distinguish between the “I” and the “He” in the poem, otherwise came closer than any of the rest of us to the ‘intended’ meaning of the poem.

Here’s what I wrote as feedback on some of the less successful answers: (it might help you to see where you’re going “wrong”!!!)

“Your job is not to translate the poem into simple English. your job is to examine how the poem communicates with us, how it creates ideas in your mind and feelings in your heart. Offer an opinion, an interpretation, not a line by line re-phrasing”

“You must integrate discussion of at least four techniques in your answer. Examine how she expresses herself as well as what she says”

“Don’t put the quote first and then comment on it. It prevents there from being any flow in your answer. Think of something to say first, then support with a relevant quotation and comment on the effect this quote has on you, if possible identifying the technique as well as the intellectual/emotional impact”

“Zoom in on individual words/lines. Don’t comment in general terms on an entire verse”

“Don’t jump around too much. Stick with your point and develop it fully before you move on”