Every year, the chief examiner in several subject areas will write up a report examining what students are doing well and how they could do better in that subject. In fact, if only just for an insight into what real report writing looks like in terms of language, layout and tone, you should read a couple of them!

The last time Leaving Cert English was the subject of one of these reports was 2008. It contains examples of student answers, with grades and commentary at the end. Before that, there was a report from 2005 and one from 2001.

This week, Leaving Cert English was once again under the spotlight. The Chief Examiner’s Report for the 2013 English has just been published and I’ve been browsing back through the various English reports to look for some trends & useful advice.

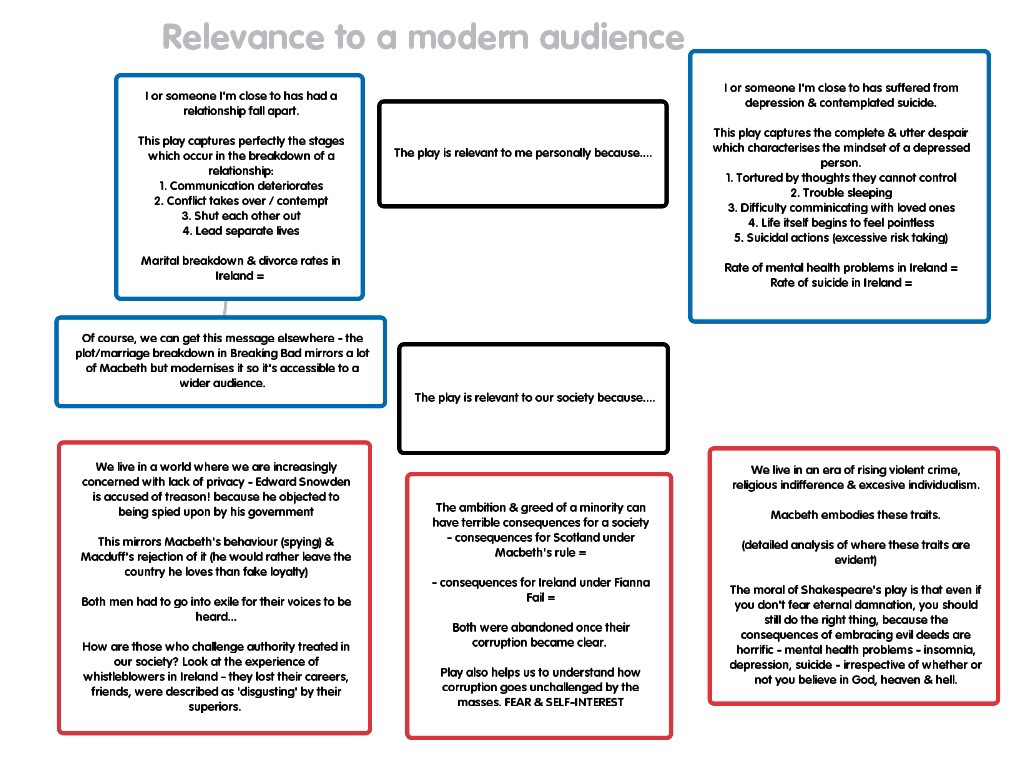

Here’s what I’ve gleaned from them:

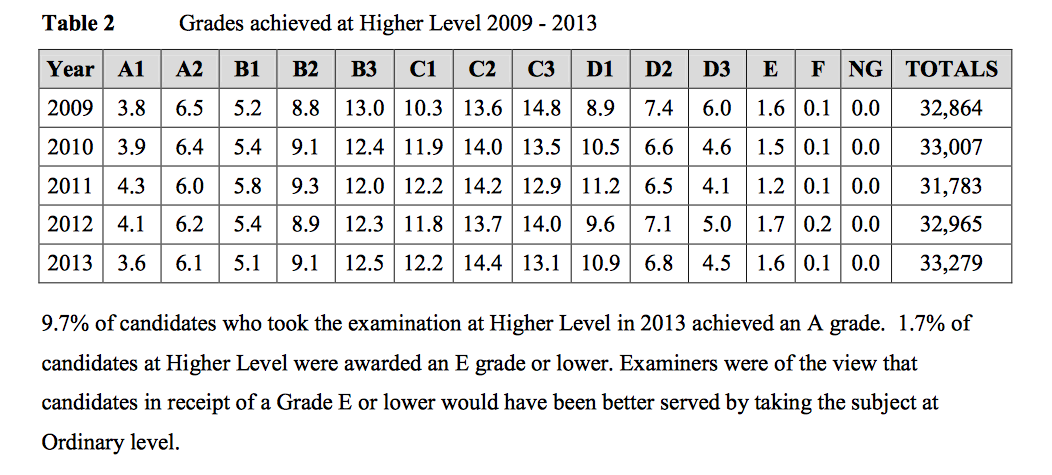

Results

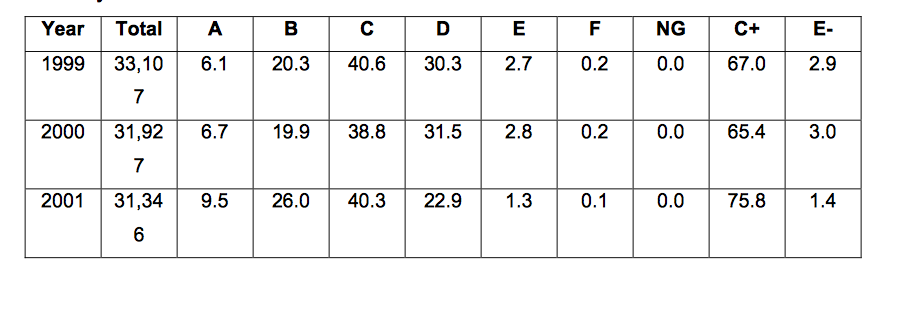

It’s pretty eye-opening to realise that 63% of students get between a D3 and a C1 in Honours Leaving Cert English. This just goes to show that getting an A or a B grade in honours English really is a great achievement. In a class of 30, this means on average you’d expect about 3 students to get an A, 8 to get a B, 12 to get a C and 7 to get a D (or if unlucky, 6 to get a D and one to fail).

However, if a higher percentage of students than normal opt for higher level, the number of students getting Ds will most likely be higher, because there are more students in the class who are borderline hon/pass and who, in another school or with another teacher, would/should have opted to sit the ordinary level paper. I find more and more students who never read and whose standard of written English is in need of a lot of work would prefer to sit the higher level paper and scrape a D2 (50 points), rather than sit the ordinary level paper and get a B2 grade (40 points), in part because of pride but mostly because it’s worth more points.

Also, the number of students getting A grades in certain wealthy middle class areas would most likely be higher than 3 in a class of 30, because students from wealthy educated homes tend to have more access to books; hear more sophisticated vocabulary; and have a greater emphasis placed on education in the home from an early age (this is not prejudice on my part, it’s proven from research and of course there are exceptions). This then has a knock on effect on the averages, so in a socially disadvantaged area, you may well have a class of 30 where no-one in the class gets an A or a B.

Speak to any teacher and they’ll tell you that every class is different and every year the results are different. I’ve had a year where 25% of the class got an A – that’s way above the norm. I’ve also had a year where no-one in my class got an A. One way to understand this on a simple level is to compare football teams from year to year. The U16s might win the All-Ireland this year; next year, with a new team in place, they might get knocked out in the first round. Occasionally what can also happen is that you’ve got a great team who just don’t perform well on the day, which is the worst thing that can happen, for the students and the teacher.

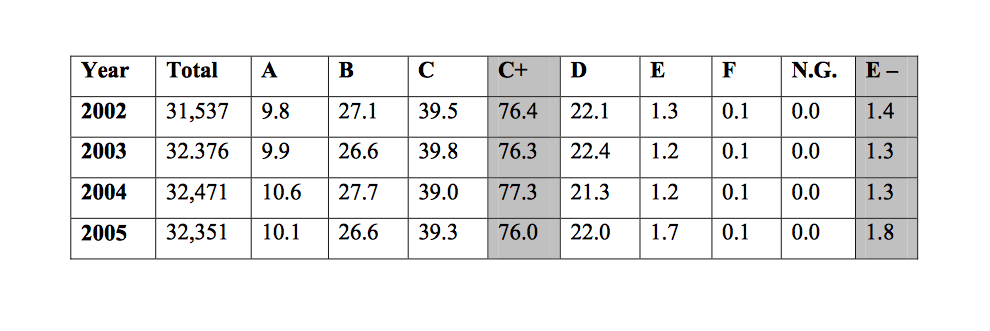

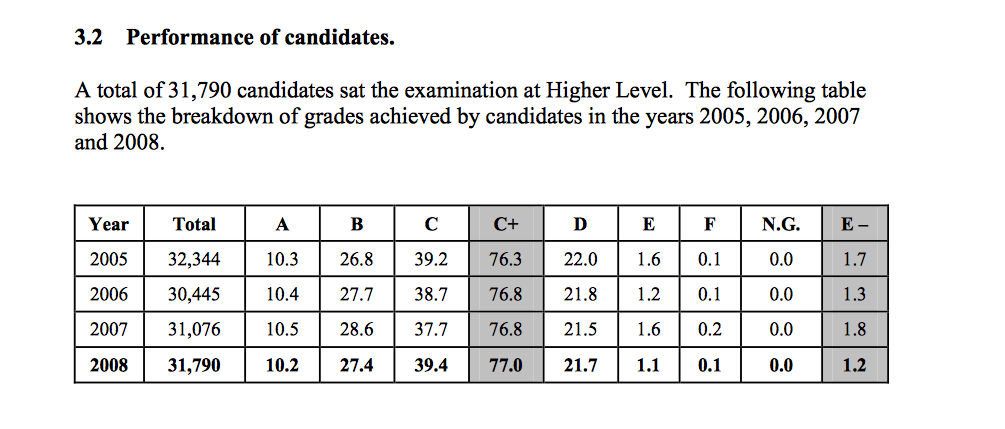

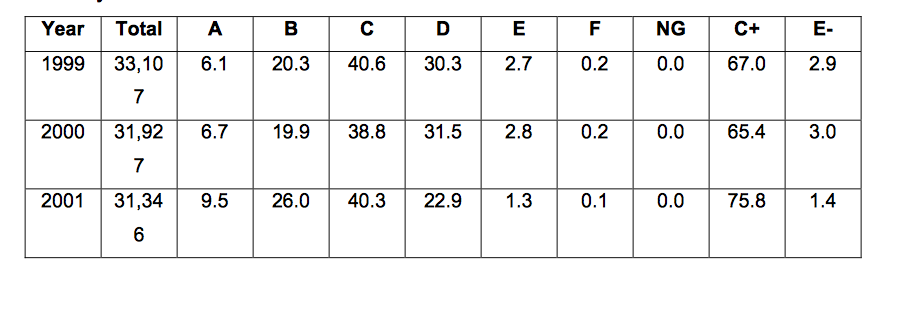

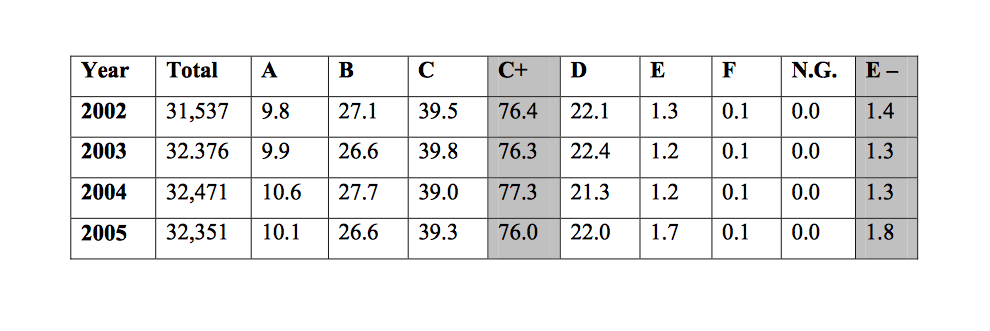

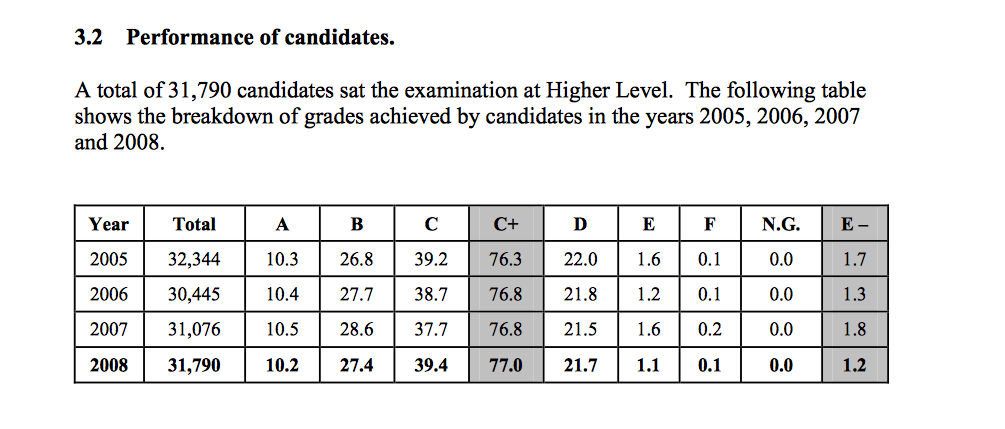

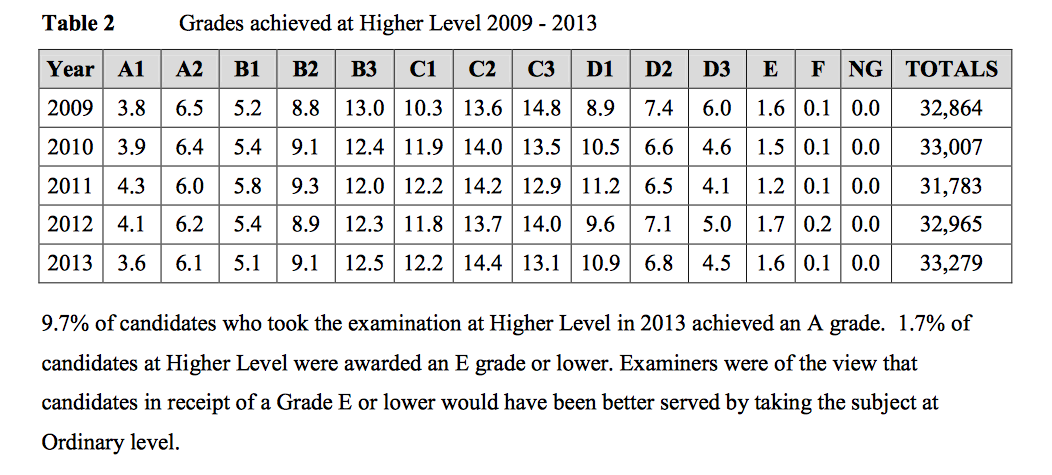

Have a look at these stats, ranging from 1999 to 2013.

I’m a little sad it doesn’t stretch back to the dark ages of 1997 when I sat my Leaving Cert but you will notice the jump from about 6% of students getting an A in 1999 to an average of 10% since the new course was introduced in 2001. It’s also interesting to note that the examiners felt that those failing the exam (about 3 out of every 200 students who sat it) should have just sat the ordinary level paper and this advice is mentioned again in the section on the rates of students taking higher and ordinary level.

Paper 1 – comprehending

Two things to note here.

The first is that you’re not just expected to “retrieve information” from comprehensions and re-phrase it in your own words, although this is one of the skills being tested. Students are also expected to “draw inferences from what they have read or seen, synthesize the material, and question or critically evaluate it, as required”. What this means is that you need to figure out what is being suggested or implied, as well as at the obvious literal meaning.

You need to demonstrate that you can stand back from the passage and see the bigger picture of the point or message the writer is trying to communicate. You must show that you can question and disagree with the writer’s opinions (if the question asks you to what extent you agree with the writer’s viewpoint) rather than simply accepting and agreeing with everything they say. You must be able to evaluate the extent to which they have been successful in communicating whatever it is they wanted to communicate and to analyse HOW they did this, in their writing style (their use of persuasive, argumentative and literary techniques).

I also liked this observation about what exactly it is you’re supposed to be doing when you read a text (but only IF the question demands it) – “relate texts to [your] own experience, generate personal meanings, discuss and justify those meanings, and express opinions coherently”

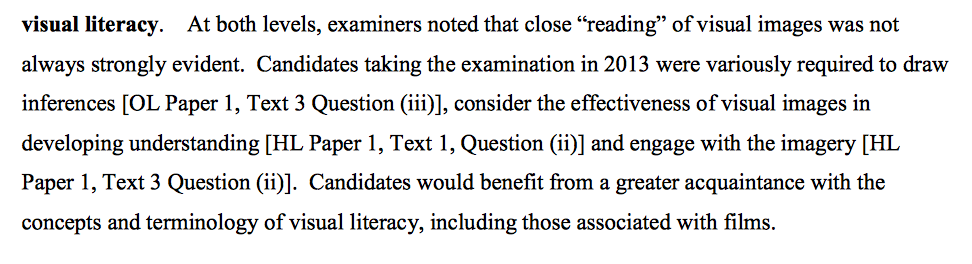

The second is that despite living in the most visual era the world has ever experienced, lots of students don’t know how to “read” images. Here’s what the report had to say on this topic:

Paper 1 – composing

The main advice was to know your genres. The report states in no uncertain terms that “It is imperative that candidates who choose to write in a particular genre be familiar with the conventions of that genre and show evidence of this knowledge in the course of their writing“. So if you choose a descriptive essay, you must write descriptively (5 senses, active verbs, adjectives, moment by moment description) . If you write a speech, you must engage with your audience, include facts, stats, quotes, embed the repetition of a key phrase. If you write a short story, you must develop plot, setting, character. The list goes on. Each genre has its own style and set of expectations.

However, I was amused to see that “skills in letter writing require attention“. I honestly didn’t know whether to laugh or cry at this one. The examiner complained that “greater attention” needed to be paid “to the rubrics appropriate to the task (e.g. return address, date, salutation and closing signature)“. I would suggest that greater attention needs to be paid to the fact that THIS IS 2014!!! For God’s sake, when is the last time a teenager any of us sat down and wrote a letter? We email, we tweet, we blog, we skype. I’m as sad as the next person that the art of letter writing is in decline, but the day of the letter is dead and gone. I think it’s about time those setting the exam took a long hard look at themselves instead of criticising kids for not giving a crap what the correct format for a letter is, when the only time they have ever or will ever write a letter is in stupid school or applying for a job, in which case they’ll google a template! Ok, sorry for the rant but I had to get that off my chest!

In other news, correctors paid compliment to students composing skills: “the best compositions were fresh, well-organised, confident responses”; “there were great examples of aesthetic writing, poetic flourishes, and well observed situations”; “the quality of dialogue and description impressed”; “it was pleasing to see the varied and imaginative ways that students were able to approach the instructions in the questions”. However, they did mention that a small number of the compositions were extremely brief and in some cases where students decided to write a short story, they failed to grasp the fundamentals that entails – characterisation, setting, dialogue, atmosphere, plot i.e. action, conflict, turning point.

A previous report – I think it was from 2008 – criticised students for going into the exam with a pre-prepared short story and writing it no matter what came up. See 7. below…

I also like the way they didn’t come straight out and say it, but the mention in no.6 of “heartfelt” articles is not a compliment. I’m willing to bet these were sickly sweet, full of cliches and made the examiners want to vomit just a little bit. Sincere can only bring you so far. Just because “that really happened” or “that’s really how I feel” does not mean it’s worth writing about.

I also like the way they didn’t come straight out and say it, but the mention in no.6 of “heartfelt” articles is not a compliment. I’m willing to bet these were sickly sweet, full of cliches and made the examiners want to vomit just a little bit. Sincere can only bring you so far. Just because “that really happened” or “that’s really how I feel” does not mean it’s worth writing about.

As for QB, “writing in the correct genre using an appropriate register” was the skill they wanted students to demonstrate and we’re told that “Examiners pay particular attention to a candidate’s efforts to tailor their writing to the audience in question and to write in an appropriate register. This may involve writing in a particular style (e.g. formal, informal, rhetorical etc) and using language appropriate to the context“. This isn’t exactly news to us teachers, but it can be difficult to get students to take enough time to figure out who their audience/readership is and what kind of language might be appropriate to this audience and this task/genre.

Paper 2 – single text

I’ll quote at length here from the report, because I think it makes a very important point which students often miss. Just because the statement is written on the exam paper, does not mean that your job is to agree with it and then just find evidence to back it up. This is actually a terrible way to approach any question. It’s dull in the extreme, simplistic and prevents you from showing off your ability to see the nuances in the texts you have studied.

Here’s what the report had to say: we “invite candidates to engage with them but not necessarily to agree, either wholly or in part, with the premise put forward in the questions. Teachers and candidates should note that while it is essential that candidates fully engage with the terms of any question attempted, challenging the terms of a question, perhaps disagreeing with some part or the entire premise outlined, is an acceptable way in which to approach an answer. Such a possibility is often encouraged by the phraseology of questions e.g. “to what extent do you agree or disagree with…”. It is catered for in the marking schemes by the inclusion of points of disputation and also by use of the term “et cetera” to cover any possible worthwhile answers offered by candidates. Examiners sometimes report that candidates can appear to adopt an overly reverential approach to questions. This can affect candidates’ ability to demonstrate skills in critical literacy“.

The other behaviour students frequently exhibit is not engaging fully with all aspects of the question asked, and lapsing into simply telling the story instead of using what they know to argue a point. Here’s what they had to say about this:

The bit about adapting knowledge is a nod to the fact that students often learn off sample answers to questions but aren’t willing or able to transform what they know so that it applies to the question asked. I wrote this blog post recently examining this very problem which you might want to check out.

Paper 2 – comparative study

There were two main criticisms, the first relating to actually engaging with the texts and the question asked in a critical way “it is possible for candidates to challenge, wholly or in part, not only the premise put forward in questions but also the views and opinions they encountered in the course of studying texts“. So same problem as above, where students feel they’re being asked to simply agree and provide evidence, when in actual fact they can agree in part, or agree in relation to some texts but not all. So we’re told that “examiners were pleased when they saw candidates trust in their own personal response and demonstrate a willingness to challenge the ‘fixed meaning’ of texts. The best answers managed to remain grounded, both in the question asked and in the texts”.

The second major criticism was similar to the complaint above about students learning off a short story and writing it no matter what came up. The same goes for the comparative where examiners complained that students had pre-prepared answers which they refused to adapt to the question asked. Don’t get confused here: in the comparative section you have to have done a lot of preparation prior to the exam. The similarities and differences are unlikely to simply occur to you on the day under exam conditions and the structure of comparing and contrasting, weaving the texts together using linking phrases and illustrating points using key moments is not something you can just DO with no practice. It’s a skill you have to learn. But you MUST be willing to change, adapt, and select from what you know to engage fully with the question asked.

This compliment, followed by a warning, was included in the 2013 report:

“Many examiners reported genuine engagement with the terms of the questions, combined with a fluid comparative approach. As in previous years, examiners also noted that a significant minority of candidates were hampered by a rigid and formulaic approach“.

A similar comment was included in the 2008 report. It seems the same problems we encounter as teachers correcting your work are appearing in exams too, unsurprisingly:

So the key to doing well is to know your texts, know the similarities and differences between them, have practiced weaving them together using linking phrases and illustrating points using key moments, but ultimately decide what to include (and leave out) AND how to phrase it on the day, depending on the question that comes up. Christ, they don’t ask a lot, do they!?!

One minor issue was students thinking they could get away with only knowing 2 texts. This is explicitly NOT the case, unless the question says “in two or more texts“. There’s no guarantee this phrase will appear, it often doesn’t, particularly at higher level, so going into the exam, you must be prepared to answer on three texts, as this is more than likely what the question will demand of you. Here’s what the report had to say: “candidates taking examinations in Leaving Certificate English should be prepared to refer to three texts in answer to questions on Paper 2, Section Two, Comparative Studies“. Also, it’s worth noting that you cannot answer on two films and you cannot include the text you’ve discussed as your single text in your comparative answer.

It also seems that there are lots of students writing comparative answers that are WAY TOO LONG. Aim for 5 pages not 9. Here’s the comment from the report which tells me that: “All candidates are reminded of the practical imperative of managing their time during the examination carefully and of the need to complete all of the requisite elements of the examination papers“. I’d say the comparative section is the main reason why students run out of time for poetry and in some cases, leave out unseen poetry altogether.

Paper 2 – poetry

Here, the problem of pre-learned off answers not being adapted to the task reared its head again.

“Candidates were most successful when they avoided a formulaic approach and demonstrated the ability to link and cross reference the work of their chosen poet in the course of an answer. The syllabus requires students at Higher Level to “study a representative selection from the work of eight poets… Normally the study of at least six poems by each poet would be expected.” Candidates who had taken the time to engage fully with the work of a poet were better placed to select judiciously, comment intelligently and respond constructively to questions posed in the examination”.

They’re also clearly arguing that if you only know three or four poems you’ll be limited in your ability to respond to the question. In other words you may have ‘left out’ the poems that are most relevant to that particular question.

The “link and cross-reference” phrase refers to the problem whereby students offer a poem by poem analysis without interlinking them, referring back to earlier poems, or emphasising the developing nature of the poets work. Your poetry essay, after all, should not be five mini essays on five different poems; it should be an integrated overview of features of the writer’s themes and style so this will inevitably involve referring backwards and forwards to poems previously discussed or about to be discussed and identifying common themes or stylistic traits as they recur or evolve.

Two more really obvious bits of advice come from previous reports, but I’ll include them here because they’re still relevant, particularly the first one:

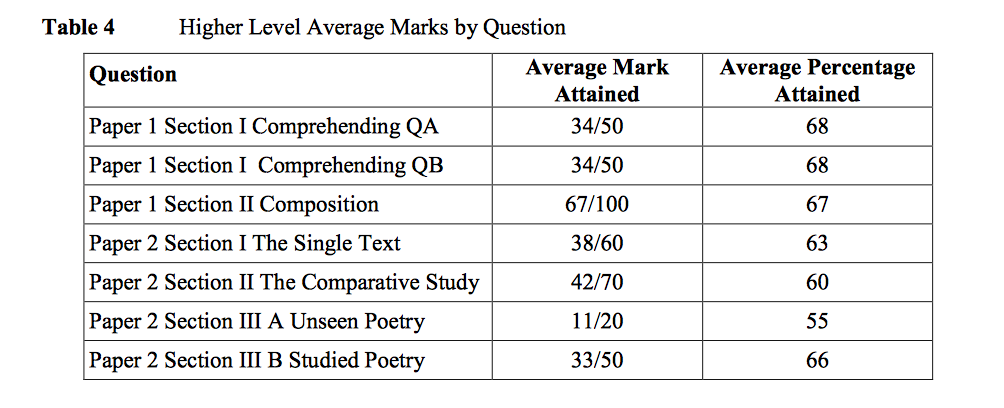

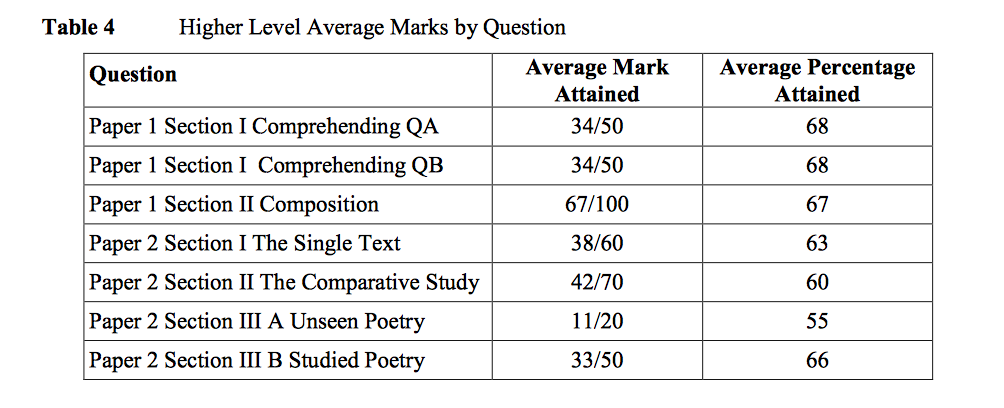

As for unseen, the problem seems to have been that quite a few students just left it out, obsessed, no doubt with getting the other sections finished. This in turn skewed the average marks achieved in each section (see below). You’ll notice unseen is the lowest. This isn’t because people do badly in this section – those who answer it generally do very well. It’s ‘easy marks’ as long as you engage with the question(s) and balance the 3T’s – theme, tone, technique, also known as ideas, feelings, writing style. But enough people got 0/20 to drag the average down to 11/20. So let me re-iterate: Students Do Well In This Section – those that answer it that is!

Conclusions

Conclusions

What we’ve suspected all along – that the comparative section is bloody hard, is reflected in lower scores. The report says “in the Comparative Study section, candidates in general scored less well here than in other sections of the examination paper. Formulaic approaches to answering questions in this section can hinder candidates by inhibiting their engagement with the terms of the questions and curtailing the expression of independent thought”.

What they don’t recognise or admit is that the demands of the genre itself – comparative analysis – are what’s leading to formulaic answers. Many students find this section next to impossible even when they have unlimited time to compose their essays. Weaving texts together is bloody difficult. Weaving three texts together and answering a set question and expressing independent thought and illustrating using key moments, but not going into too much detail in case you spend too long on one text and then get penalised for not weaving, comparing and contrasting enough with limited time under exam conditions is a head wreck of mammoth proportions!

The results are lower because it’s the most difficult section. There’s no mystery here. It’s just BLOODY HARD…

I mentioned earlier that the stats don’t go back to 1997 when I did my leaving cert. Back then I got an A1 (which redeemed the B in Junior Cert English that I found personally devastating) but the comparative didn’t exist. I’d love to sit the exam again for the hell of it and see how I’d get on. I’m confident I’d get an A1 again in every section except possibly the 100 mark composition (it’d depend largely on getting a topic that suited me and I’d find handwriting rather than typing infuriating in the extreme) and definitely the comparative, where I might scrape a B1, but only if things went well on the day. Are you getting the vibe that I hate the comparative? Yeah, I kinda do.

In more general terms, there’s no substitute for fluid but controlled sentence and paragraph structure, complex but accurate vocab, good spelling and grammar and fluency and flow with language.

These are things your teacher can attempt to teach you but the roots of this go deep deep into the vaults of your past (How much do you read? Did you read a lot growing up? Did your parents talk to you a lot using complex vocab?) and also reflect your personality. Do you actually and have you ever cared about planning and structuring your work? Do you and have you for the past 6 years checked your spelling or do you just fling down any oul guess? Do your thoughts appear in random disconnected bullet points or do they flow one into the other like a living stream of language?

These are things your teacher can attempt to teach you but the roots of this go deep deep into the vaults of your past (How much do you read? Did you read a lot growing up? Did your parents talk to you a lot using complex vocab?) and also reflect your personality. Do you actually and have you ever cared about planning and structuring your work? Do you and have you for the past 6 years checked your spelling or do you just fling down any oul guess? Do your thoughts appear in random disconnected bullet points or do they flow one into the other like a living stream of language?

Two more final observations.

You can’t do well in English by just learning loads of stuff off. This can be hard for students to accept, particularly because I’m told there are some subjects (but I wouldn’t dare name them!) where learning stuff off and vomiting it back up is rewarded. English is not one of them. You can know a lot but still do badly if you can’t express your knowledge in a coherent way. One of the reports identified this by saying that “some examiners identified candidates who were able to demonstrate knowledge of a text or texts but were less able to deliver this knowledge in a lucid or coherent fashion“. Ultimately, if your points are unclear, or unrelated to the question, you won’t be rewarded for simply knowing stuff.

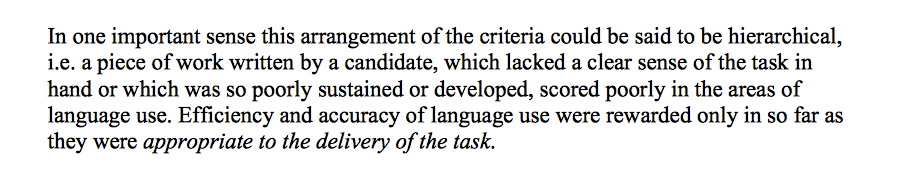

Finally, finally, finally. The marking scheme PCLM stands for purpose, coherence, language, mechanics. But no matter how beautifully written something is, if it’s not relevant to the question/task (Purpose) then it won’t make any sense (Coherence) and you won’t get good marks for writing well (Language / Mechanics) if it’s completely off task / off topic. This wasn’t referenced in the most recent report but it did appear previously, the idea that your mark for P dictates your mark in the other sections C L & to a lesser extent M.

So???

So???

OBEY THE DEMANDS OF THE QUESTION.

That’s the best advice I or any teacher can give you.

THE TASK MUST BE OBEYED! THE QUESTION IS KING!

WORSHIP IT.